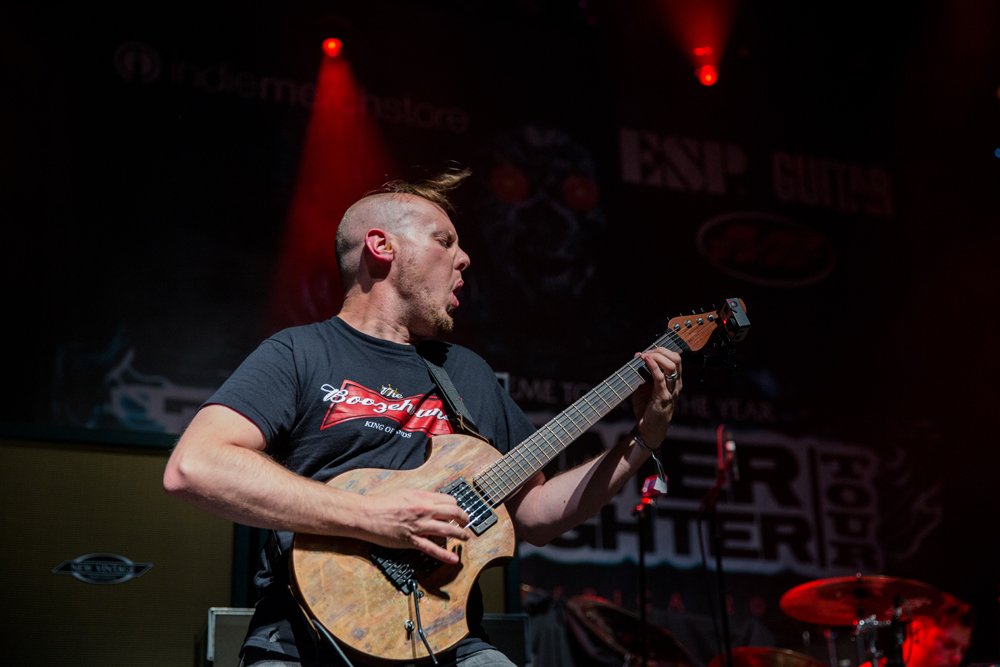

Josh Elmore of Cattle Decapitation on Touring, Time, and Curiosity

There is something faintly perverse about a band as forward-driven and restlessly self-critical as Cattle Decapitation deciding to look backward—especially when the object of that reflection is an album barely old enough to have accrued myth. Death Atlas is not a legacy record in the classic sense. It is not a nostalgic waypoint or a fan-service exercise in historical reenactment. And yet, six years on, it has quietly asserted itself as a gravitational center in the band’s catalog: conceptually expansive, emotionally punishing, and structurally demanding in ways that still feel unresolved rather than embalmed.

The idea of touring an album in full has become increasingly normalized, often marketed as reverence—sometimes barely disguised as data-driven pragmatism. In metal, where repetition is both a virtue and a trap, the line between honoring a record and exhausting it can be perilously thin. For guitarist Josh Elmore, that tension is not abstract. It cuts to the core of how bands survive the modern touring economy without flattening themselves into content loops or nostalgia acts, and how artistic intention is negotiated amid metrics, management strategies, and the quiet fear of becoming predictable.

Elmore speaks with the wary clarity of someone who has watched multiple industry models rise, collapse, and resurrect themselves under new branding. His skepticism isn’t performative; it’s structural. Whether discussing why Death Atlas—rather than the fan-anointed Monolith of Inhumanity—became the focal point of this tour, or how streaming data increasingly dictates artistic framing, he remains less interested in validation than in coherence. What matters is not whether a decision is popular, but whether it is defensible—musically, logistically, and psychologically.

That same rigor extends inward, to the mechanics of the band itself. Elmore’s reflections on relearning Death Atlas, reconstructing forgotten muscle memory, and navigating lineup changes are less about sentimentality than systems: how songs are written, abandoned, rediscovered, and finally reassembled under the pressure of time. His approach to guitar work—favoring texture, restraint, and atmosphere alongside violence—mirrors his broader philosophy. Excess, whether technical or conceptual, must justify itself.

In the conversation that follows, Elmore traces these ideas with a candor that resists easy mythmaking. This is not an artist mythologizing endurance or romanticizing struggle. It is a craftsman taking inventory—of records, relationships, habits, and instincts—while standing in the middle of a career long enough to feel the weight of continuity, but not so long that curiosity has hardened into ritual.

J. Donovan Malley (for FMP): I’m interested in the idea of touring behind an entire album—Death Atlas in particular. The first time I remember seeing this outside metal was when Sonic Youth played Daydream Nation in full. Talk to me about the thought process behind this tour and the decision to focus on Death Atlas.

Josh Elmore: I always thought album tours were something you did once a record had become a “classic,” after decades had passed. So doing that with an album that’s only six years old felt strange to me.

What’s funny is that this tour was actually planned by our old management back in February. Their feeling was that we’d toured Terrasite enough and should move toward a more traditional release cycle—an album every couple of years, like a lot of younger bands do now. I get that logic, and it wasn’t about management or the label interfering. They believe in us and thought that was the best path forward.

But we wanted to keep touring. And when you look at it, we actually hadn’t done that much for Terrasite. It came out in May 2023 while we were already on the Decibel tour. Then we did a run with Immolation and Sanguisugabogg that November, Europe in early 2024, Chaos & Carnage in May–June, another European run in early 2025—and then nothing.

Management’s view was that if we were going to tour again, it should be about something—not just another Terrasite tour. There’s a balance there, because bands can absolutely tour themselves into the ground. At some point, people start thinking, “I’ll just catch them next time,” and that perception snowballs until you’ve played yourself out.

FMP: That seems like a hard balance to strike.

Elmore: It is. You’re balancing that against everyone’s personal lives and your writing cycle. So management suggested making the tour an event, and brought up the idea of playing an album in full. We hadn’t seriously considered that before.

Then the question became: which album? Is it purely metrics—streams, sales, that kind of thing? That’s one way to approach it, and by those numbers, Death Atlas was the clear answer.

At first, I assumed it would be Monolith of Inhumanity, because everyone wants Monolith. But once that was taken off the table, Death Atlas stood out by a significant margin. Terrasite hadn’t been out long enough to build those numbers, and The Anthropocene Extinction—which we all love—is kind of the dark horse of the last four albums.

FMP: It’s your Fair Warning.

Elmore: Exactly. That’s perfect. The one we really fucking love—but it wasn’t the one. So once it was Death Atlas, that settled it.

We’d played most of the record live already, but there were three songs we’d never played. Not for any dramatic reason—just because certain tracks naturally became staples. You’ve got “Bring Back The Plague,” “One Day Closer to The End of The World,” the title track, “Geocide,” and “Finish Them.” Those were the logical ones.

That left “With All Disrespect,” “Be Still Our Bleeding Hearts,” and “Absolute Destitute.” So everyone had to do their homework individually, then come together.

FMP: Did that mean relearning material? I’ve talked to bands who say they’re watching YouTube videos of other people playing their own songs.

Elmore: Oh yeah. You watch these people who surgically dissect your song and play it perfectly, and you’re like, “I have no idea what I was doing there.”

You put yourself in their shoes, kick yourself for not remembering it, and then just watch how they do it. I listened to everything and played along. Some parts I had to go back to a few times because in the mix, it’s not obvious what I was doing—especially with how my parts interact with what Bell is doing.

We all showed up in San Diego a couple of days before the tour started and just ran the songs. There were a few bumps because we hadn’t played them together, but overall it was fine.

“With All Disrespect” was the first song we wrote for Death Atlas. That was probably late 2018. You write the first song, record it, then move on. You learn it just enough to track it—and then you basically forget it.

In the studio, you’re recording in parts. You don’t always practice the full song start to finish the way it exists on the record. So years later, you come back and have to glue all those ideas together.

FMP: When you record solos, are you stitching together multiple takes?

Elmore: Yeah. Sometimes you go in with an elaborate idea, but it ends up being busy rather than effective. I’ve always believed at least part of a solo should be something you can hum—an earworm.

There’s always going to be shreddy stuff, but I want something tuneful in there. A lot of it comes down to what sounds best in the moment. Sometimes you get a long, flowing take and punch in the end. Other times, you have to chop it into pieces.

Ideally, you’d do it all in one shot—but depending on what you’re playing, that can be incredibly difficult. I have infinite respect for people who can do that consistently. And it’s even harder for the engineer to make a chopped solo sound seamless.

I’ve talked to players who’ll say, “That took 50 takes.” They’ve had months to practice it for live performance, but in the studio, it’s about capturing something that works.

FMP: Losing a member and bringing in someone new is always a big shift. Talk to me about Oli leaving and where things stand now.

Elmore: We love Oli. He was juggling our band, Cryptopsy, and his own projects, and Cryptopsy has been his family for a long time. As they became more active, he had to go with his heart. I don’t blame him at all. We miss him dearly. He was a key member for a long time—an incredible bass player and a great presence onstage. But we respect his decision completely.

Some people can manage two full-time bands. I couldn’t.

FMP: It closes off a lot of personal-life options too.

Elmore: Absolutely. Relationships become harder. Financial stability becomes harder. It’s a tricky balance between being active enough and respecting everyone’s personal lives. If either side collapses, it’s hard on everyone.

FMP: And Diego (Soria, the band’s current bassist)?

Elmore: He’s been great. He’d helped us out before when tours overlapped, and there were shows where he just showed up and played without having rehearsed with us at all. After Shockfest we had a meeting in October, and it’s been really smooth. It’s been fun.

FMP: Are you already thinking about what comes next musically?

Elmore: Yeah, we are. The old model—tour for years, then take eight months to write and record—doesn’t really exist anymore. There’s pressure to have new material constantly.

We started writing in September 2024, and I really like what we came up with. Life happens, though, and suddenly it’s a year later. But on this tour, we’ve been sharing ideas constantly—dumping riffs into a shared interface, building things remotely. That’s new for us.

Some bands write entirely online. We’re not there, but we’re incorporating more of that. We’ve got a solid springboard, and a lot of strong core ideas to build around.

Personally, I’d like to explore more clean guitar textures—still heavy, still brutal, but with more ambient, darkwave-ish elements nested inside the songs. That stuff is already on Terrasite, and I think it’ll be more fully realized next time.

I’d also love to make the next record more compact. The last few albums have been long, which I don’t regret—but the idea of twelve absolute bangers, four-and-a-half minutes each, really appeals to me.

FMP: You and Travis have been working together a long time now. How do you keep that relationship functional for decades?

Elmore: We stay in our lanes. He’s deeply involved in the conceptual side—lyrics, artwork, themes. Musically, it’s mostly me and whoever else is in the band at the time.

We respect each other’s vision. He might hear something and suggest changes for vocal flow, but there’s a lot of trust. You don’t see the full picture until late in the process, and it’s usually pleasantly surprising.

That trust has built over time. At this point, after so many years, you know it’s going to make sense—even if it doesn’t immediately.

FMP: What’s one way you’ve changed significantly as a songwriter—and one thing that’s stayed the same?

Elmore: Early on, I was all forward momentum. Get the idea down, move on. Now I almost overthink everything—revising endlessly, putting the jeweler’s eyepiece on it. I’ve also shifted from being a million-notes grindcore player to being more interested in space, texture, and mood. The interaction between effects, notes, and placement has become really compelling to me. Even the simplest part can sound profound if it’s done right.

What’s stayed the same is this instinct to explore—to try the weird regional candy bar instead of the Snickers. I don’t know why I’m wired that way, but I always want to see what’s there. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t—but that curiosity has never gone away. And that's the thing: getting comfortable with that–comfortable in our skin, knowing ourselves, and making it work. Accepting certain things and then working on other stuff.